A Way of Man (Miehen Tie) - a Nobel-winning work that doesn't exist in English

Taata. It happens every time: we find treasure, as I found Silja, one of the great diamonds of Literature, and become fans of its creator, check out everything written by the same hand hoping to reexperience the magic of catharsis. A Way of Man is a great read. Next year I'll be rereading Silja. Then again I'll read another of your stories, even though I know it already: it will always be Silja that I reread.

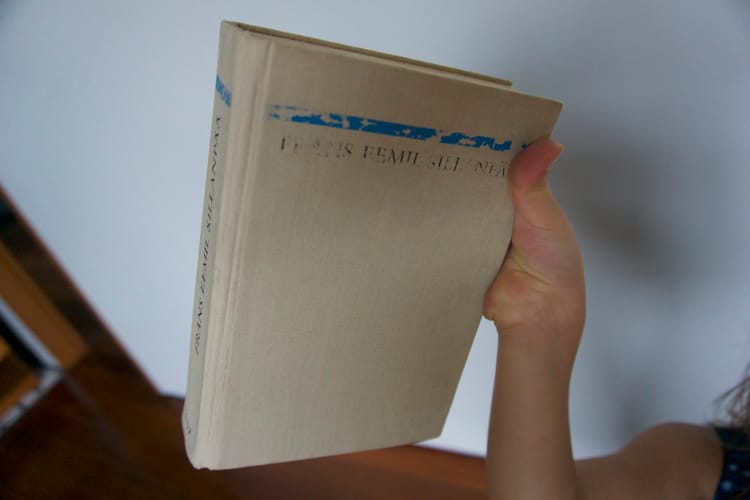

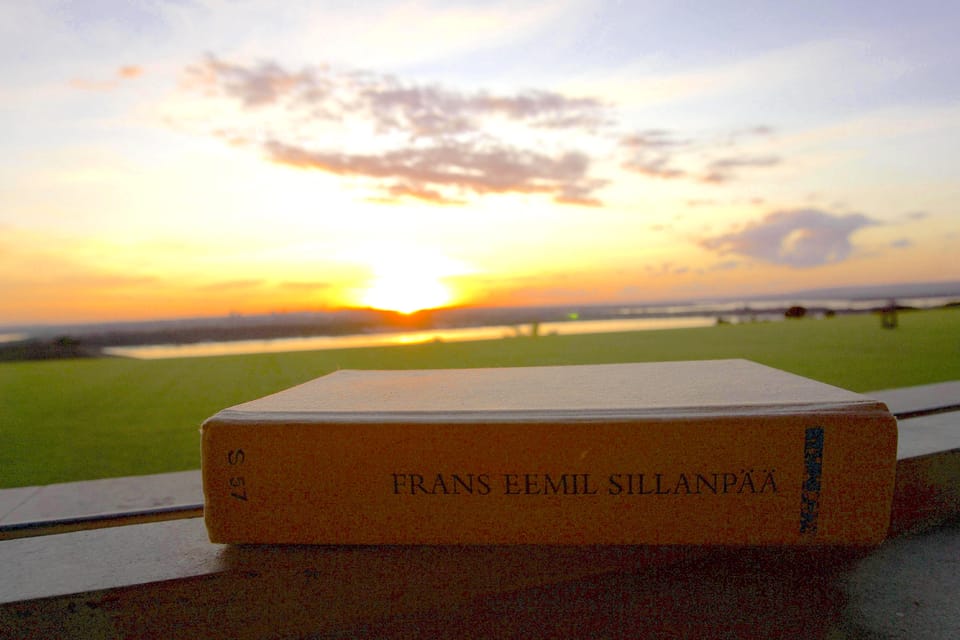

I am rich. I have a collection of novels by Finland's only Nobel Prize Laureate in Literature. Three of Frans Eemil Sillanpää's greatest stories in one book. They are brilliant translations from 1981, from Finnish to Hungarian by Irén N. Sebestyén: Nuorena Nukkunut (The Maid Silja, 1931), followed by Miehen Tie (A Way of a Man, 1932) and Ihmiset Suviyössä (People in the Summer Night, 1934).

I'm also rich because I possess the knowledge of Hungarian, possibly the best language for a Finnish book to be translated into. (Linguists may debate on just how closely related these two so-called Finno-Ugric languages are but A. they are closer to each other than to any other languages in the world (besides Estonian) and B. having lived in Finland for almost a year, I can attest that the Hungarian and the Finnish souls are closely related enough.) I only found out that A Way of Man, one of the major works of Nobel Prize winner Frans Eemil Sillanpää has not been translated into English when I started to work on this review. I'm richer than I thought I was, and yet I start feeling sad about it.

You can always JUMP TO REVIEW on A Way of Man, or you can hear the curious story of how Sillanpää's art found me, a story that I'm not afraid to share even though I should be. I'm not saying that I stole the book but I'm saying something along those lines. Will tell you in a second.

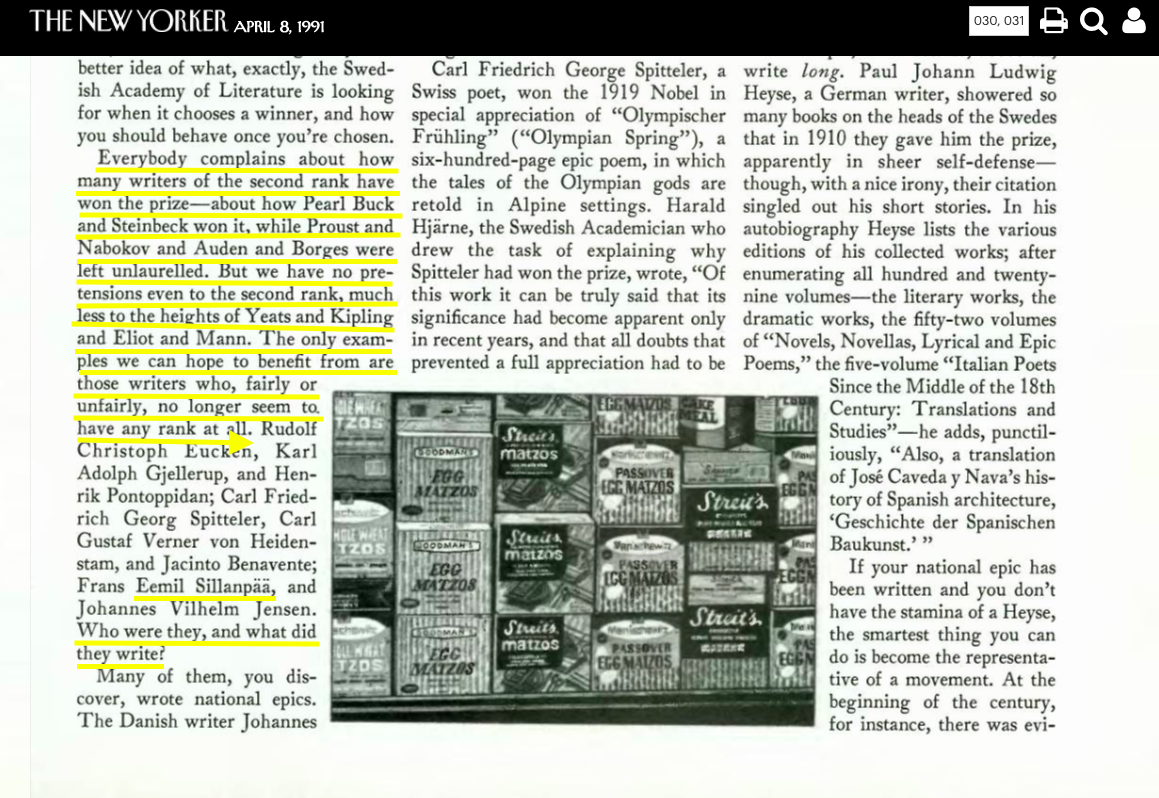

But first I'll take that second to tell Mr. Adam Gopnik, staff writer of The New Yorker, with all due respect that his missing out on Frans Eemil Sillanpää's novels must have been a warning sign NOT to cover any of it.

"Who is Frans Eemil Sillanpää and what did he write?"

is Mr. Adam Gopnik's question -- he applies it to those Nobel Prize Laureates in Literature who, as he puts it, "fairly or unfairly, no longer seem to have any rank at all."

Now, if Mr. Adam Gopnik had read a Sillanpää novel or two, he could have just found himself in a position to cross the cultural bridge between the Manhattan skyscraper of The New Yorker and the clover fields of Kierikkala village, and tell me, a The New Yorker subscriber, whether Sillanpää disappeared from public consciousness fairly or unfairly. As it is the only question of interest in such a story for such a magazine. Yet apparently Mr. Gopnik read the wrong book “from cover to cover". The book he used as his main source for his The Talk of the Town Comment to discuss the chances of a writer to be awarded with a Nobel Prize in Literature, was "Nobel Lectures: Literature, 1901-1967."

Many more interesting questions come to mind than: Could anyone be one of the best writers ever lived, if New Yorkers never heard of him? Among those questions are:

- How is it even possible that only three out of seven novels of a Nobel Laureate are translated into the ruling language of the world?

- Only a few short stories out of ten short story collections?

- None of his three memoirs?

- The main autobiography written on him is not available in English?

We put so much money, expectations and hope (rightfully so) into upcoming literary talents to see them flourish, to give them all the help to see them becoming a Nobel Laureate one day, while in the meantime we let the names of those who already proved their amazing talent sink into oblivion? Instead of reading the works of Nobel Laureates we read articles about how some of them MIGHT not be relevant today?

- How is it possible that the English translation of Sillanpää's most popular work Silja has been criticised but never retranslated?

- Is Sillanpää not worthy for international discussions or is he getting unfair treatment because he only truly exists in the Finnish culture?

Trust me, coming from a small nation of less than 10 million, I don't think too much of the Nobel Prize in Literature either. I don't think too much of it because Zsigmond Moricz (the Hungarian Sillanpää, who could have just as well received a Nobel Prize "for his exquisite art in painting the peasant life and nature of his country") and Endre Ady and Attila Jozsef, giants of Poetry -- never received such a prize. It's debatable whether they could give international readers the kind of catharsis they give Hungarians, but then it's debatable for Hemingway's work too. Yes. I'm someone who thinks making a distinction between art that speaks for one nation only and art that speaks to "mankind at large" is idiotic. Art at its best speaks to mankind. Period. Smaller nations need better translators. Hungarian and Finnish authors need translators who are artists themselves.

Among all the sceptics of the Nobel Prize in Literature in the year of 1939, the biggest sceptic was Sillanpää himself. Even though his name had been on the Nobel table as a potential awardee ever since he wrote Meek Heritage in 1919, he too, was certain that he only actually won the Nobel because Sweden had wanted to give the prize to Finland that year as a gesture of solidarity for their heroic fight against the U.S.S.R.

"This Prize is due my country as much as to me."

is said to be Sillanpää's first remark at a press conference.

Two years later in the spring of 1942, he wrote:

"Darkness closes in. On the table in front of me is an old magazine, a whole page is covered with illustrations relating to me, and the text on the opposite page tells about me. From all this I gather I was awarded the Nobel Prize. I even learn that I was present and received it."

(Nobel Prize Library, 1971)

Who is Frans Eemil Sillanpää and what did he write?

For basic facts read his autobiographer, Panu Rajala's summary.

Proving Mr. Adam Gopnik's point: Up until two years ago, I've never heard of Frans Eemil Sillanpää. His book found me, not the other way round.

I am a true believer that the best books find us at the best moment. They just do.

It was at the height of the summer in a quiet Hungarian village surrounded by vineyards and corn farms at Lake Balaton - a scenery straight out of a Sillanpää novel. My grandparents had a peasant cottage on the top of the medieval castle hill in that tiny village, Szigliget. My grandmother (who had something important in common with Louisa May Alcott) took me to this village every summer. The first time I was only 4. One of our favorite pastimes was visiting the library, which occupied two rooms in the local school, and we would climb the hill back to the cottage with our backpacks filled with books.

Twenty years after our first summer there I lost my grandmother. She couldn't get to see the local library getting downsized. Someone in charge decided to get rid of most of its collection. Don't ask questions. Neither did I. There are times when one cannot ask any questions. In Hungary it is most of the time. A couple of hundred books were doomed to be destroyed, thrown into a tiny storage place. The librarian (who used to know the late librarian who had known me as a 4-year-old) let me in the storage to take whatever I fancied. Frans Eemil Sillanpää's book was lying there, waiting to be destroyed (proving the point of Mr. Adam Gopnik, again).

It was an old, ivory white, hardcover book with one stripe in my favorite blue crossing its body on the top evoking the flag of Finland. The blue stripe started to fade away as did the name of the author, the only text on the cover. I took it in my hands, dusted it, smelled it. Even in its dilapidated state the book looked valuable, published by Hungary's most prestigious publisher in 1981. The author was Finnish -- I have a special bond with everything Finnish having lived in Helsinki for nearly a year as an English major student of Helsingin Yliopisto. I got curious. I glanced at the epilogue: Sillanpää was the only Finnish writer who won the Nobel Prize.

A thrown out book from Finland whose author I've never heard of but received the Nobel Prize - things that make me want to read a book.

So I did. I started with the first novel in the collection: Silja. It turned out to be a gem of a story about the tragic fate of a peasant girl. Think of a Tess of the D'Urbervilles in Finland. This year I continued it with A Way of Man, a coming of age story of Paavo Ahrola, a man with a difficult childhood who learns how to stand firm on his own feet and makes his own fortune but still need to learn how to love.

What is mindblowing about Sillanpää's art is that so many of his works are regarded to be the "most important" depending on who reviews them.

-

Sillanpää received the Nobel for Silja, according to Sari Karig, the editor of my Sillanpää collection and also Per Hallström, Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy (1931-41). Silja, no doubt about it, is Sillanpää's most celebrated work. (The only readers who did not celebrate it were the sceptical English critics, see below).

-

Then there is People in the Summer Night, that various Finnish literature experts, such as Petri Liukkonen, the creator of the brilliant Authors'Calendar and Panu Rajala, Sillanpää's biographer call as Sillanpää's most important work.

-

Meek Heritage*, Sillanpää's second novel, which takes place during the Finnish Civil War, is called by the Encyclopedia Britannica as his most significant novel, and Rajala calls it the most enduring one of all.

-

Sillanpää himself regarded Hiltu and Ragnar (Hiltu ja Ragnar, 1923) - a short story about an attraction between a 'gentleboy' and a servant girl going tragic, his best work.

Never seen such dissensus about the best work of a classic writer. Not to mention most of his short stories, which, as of today, don't exist in English. Sillanpää might well be one of the least known best storytellers in history. Looks like I have the best of his works still waiting for me to discover provided that I find them translated.

"We are becoming fussy about our writing and reading. Mr. Sillanpää is a very useful antidote to intellectual fuss. It is all very slow and moving and lyrical. Obviously a good book. But not, perhaps, a supremely good book."

(Harold Nicolson’s review in the Daily Telegraph of Silja, 1933)

If you are still with me here, here are my thoughts on A Way of Man:

- A Way of Man shares a lot in common with Silja:

- its story being as much about Nature and Humans as about Men and Women, birth and death, attraction and sex, pride and principles, love and indifference. Everything that truly matters in life is distilled in this short piece of art.

A Way Of Man's anti-hero Paavo Ahrola knocks up a village girl then doesn't marry her. He marries someone else. He sends money to the mother of his first child but his money is not wanted: "How does Mr. Paavo know if the child is his?" the pride response arrives. Later Paavo lives through tragic events, events that no one, not even irresponsible cowards as himself deserve. He is hated by people he doesn't care about, and loved by people he doesn't care about. He learns that the only person he cares about is the village girl whom he betrayed. Will he find peace and redemption? Will he ever get to know his child who he abandoned? Or will he die as a lonely drunkard, a character who Sillanpää might have modeled on himself?

Good stories only need a few intriguing questions.

- its beautiful language as clear as a mountain stream (see excerpt below), its breathtaking ways of expressing a thought -- must be a Fin-thing that works brilliantly in Hungarian. I hope it works in other languages just as well. I'm hearing that Finnish is all but impossible to translate into English. Not shocked. The Hungarian spirit is also quite un-translatable to English. (See: this blog in its entirety.)

"There is almost no summer night in the north; only a lingering evening, darkening slightly as it lingers, but even this darkening has its ineffable clarity. It is the approaching presentiment of the summer morning. When the music of late evening has sunk to a violet, dusky pianissimo, so delicate that it lengthens into a brief rest, then the first violin awakens with a soft, high cadence in which the cello soon joins, and this inwardly perceived tone picture is supported outwardly by a thousand-tongued accompaniment twittering from a myriad of branches and from the heights of the air. It is already morning, yet a moment ago it was still evening."

(People in the Summer Night, translated by Alan Blair)

Dear Sillanpää. I already miss his words. When you catch yourself missing the words of a book upon finishing it, you know that it's a book you are going to reread. You know that it's a book that creates a world you can call home.

- Sillanpää shares something in common with Hemingway:

Sillanpää's magic-making in regards to the importance of omission is similar to Hemingway's. Sillanpää does the exact same magic with narrative sentences that Hemingway does with dialogues: only half of the story is on paper. The other half is written by us -- the reader is forced to create it. While in Sillanpää's stories most actions, their significance and exact meaning are explained at some point in the text in a way Hemingway would have never given away any clues, right in the moment in Sillanpää's story too, it is the reader who has to fill in the gaps.

No trace of Hemingway reading anything from Sillanpää... Mr. Adam Gopnik's reasoning is one answer. Except that I kind of feel Hemingway would have loved Silja too. He might have put it on his list of essential readings and would have changed the fate of Sillanpää's books so that The New Yorker would have had its article on loser Nobel Prize Laureates without Sillanpää on the list.

- I did skip a page or two of nature description (Sillanpää's forte) on the last pages when all I cared about was whether Paavo Ahrola would man up to apologize to the peasant woman he betrayed and left with his child. At that point I couldn't care less about what magic Spring brings out of Nature, as a matter of fact I was frustrated that Sillanpää took the courage to go into detailed nature descriptions at the climax of the story. So I skipped the parts about the shape of the Moon and the smell of the clover field and finished the story. Then I went back. I went back and read those wordy descriptions. 'Cause those words are gold.

"Many pages seem to be written not on nature, but from its point of view, and that's a big difference. As if Sillanpaa would view men from a non-human world, and to me, this is a very modern escape from traditional psychology in novel writing, one that's deeply rooted in the northern experience."

(Philippe Levreaud, avid Sillanpää reader on Life and the Sun (Elämä ja aurinko, 1916), Sillanpää's first novel)

Read Sillanpää. Whichever of his works is available from the extremely limited resources. I give you the best reason to do just that, Sillanpää's words, that he said upon winning the award:

"I feel deep joy that I can render my country the greatest service and old author can render it...that of increasing the world's respect for Finnish culture and helping to make the voice of the Finnish spirit heard in the world.

🌲❄️🧖💙🔥🇫🇮

Summary:

-

Will I ever reread this book?

I already did. Also, I reread Sillanpää's Silja every year.

2/3 -

How quickly I got sucked into it?

Very soon. Unrequited love stories do that to me.

2/3 -

How easy is it to read (grammar, style, highbrow/lowbrow)?

Easy, yet beautifully written.

3/3 -

Difficult to put it down?

Yes.

3/3 -

Did I cry?

Yes.

3/3 -

Did I laugh?

Yes

3/3 -

How timeless?

We are deep into the era of global warming today but Sillanpää's art which focuses on Finnish nature is still true. As for relationships between human beings: also still true.

3/3 -

Catharsis?

Only with Silja.

0/3 -

Is it worth living without reading this story?

Maybe. It's easy for me to say it though: I already read A Way of Man.

1/3

20/27 =

- Read this book, if it's available in your language. It's worth it. It's a great summer read, while sun-bathing and munching on fruits and challah bread with Nutella.

- Read Silja before A Way of Man.

- Read A Way of a Man before Little Women (unless you are a female reader in your teens looking for worlds to escape, in which case take Little Women ahead of anything else.)

Comparing novels is idiotic (only ranking good books on the same 1-5 star rating scale is more idiotic): there is no right order for good books, but in the urge of expressing my feelings for the books participating in the Hemingway-challenge and beyond, I make suggestions which one to read first. We don't have enough time on this earth even for reading.

P.S.

-

Here is where to find Meek Heritage , 1919, a translated Sillanpää novel online for free.

-

And The Lake (Järvi), 1915, one of his numerous short stories.

-

If you read Hungarian (I know about the chances), and Sillanpää's literary fate make you wonder about the nature of success, couple your readings with my essay on how Brazilians define success.